Autism & Community

This blog marks the beginning of my unmasking journey in relation to my autism. Community and belonging have always felt elusive to me, even from childhood. I often felt like an outsider — observing rather than participating — with the unspoken expectation that acceptance must be earned through hard work, conformity, and effort. Over time, I have come to understand this expectation as both unrealistic and harmful, particularly for neurodivergent individuals.

I am not alone in this experience. Recently, I had the opportunity to hear Lee Chambers, an autistic speaker, discuss the dangers of overworking to gain self-worth and the toll it takes on mental health. His insights affirmed my experiences and motivated me to explore these ideas more publicly.

In this piece, I aim to challenge the commonly held belief that community is inherently safe or free. I propose instead that, particularly in modern capitalist societies, community can be based on exploitation — especially of those with less social power. Through my lens as a Black autistic woman, I offer these arguments:

- Community is not free.

- Community is not always safe.

- Community Will Make You Wrong for Responding to It

- Community Will Cost You Everything

Argument 1: Community is not free

Anthropologists often argue that community has historically been critical to human survival. Yuval Noah Harari, in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, states:

“People with strong families who live in tight-knit and supportive communities are significantly happier than those who are isolated.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “community” as “a group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common.”

However, in modern society — particularly under capitalism — maintaining community often relies on unpaid, invisible labour, primarily undertaken by women. According to a 2023 study by Work and Opportunities for Women, unpaid care and domestic work would account for 9% of global GDP if it were compensated. In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (2015) estimated the value of young women’s unpaid work at £140 billion annually.

This unpaid labour extends into religious, charitable, and informal community spaces, where women dominate volunteer work. In a society that values busyness and productivity, unpaid community labour becomes exploitative rather than empowering.

Even within heteronormative romantic relationships, studies show women tend to lose leisure time and accumulate more domestic responsibilities, leading to long-term health consequences. Conversations around these inequities have become more mainstream, visible in movements such as:

- 4B Movement: Originating in South Korea, advocating for women to reject traditional relationships that centre male benefit.

- Sprinkle Sprinkle Movement: Popularised by Shera Seven, encouraging women to value their labour and not financially invest in dating.

- Decentralising Men: A social media-driven conversation encouraging women to challenge internalised patriarchal norms.

Attempts have been made to redistribute this unpaid burden, such as Eve Rodsky’s Fair Play system. However, these often fall short, requiring women to project-manage change — still placing emotional and organisational labour primarily on them.

From personal experience, I recall volunteering extensively alongside full-time work, believing that doing “enough” would eventually shield me from further demands. Instead, the nature of exploitative structures meant that more was always asked, without regard for personal boundaries or wellbeing.

Thus, under capitalism, community often functions not as a nurturing space but as a structure dependent on unacknowledged, unpaid labour — particularly from women.

Argument 2: Community is not always safe

Safety within communities is not guaranteed — especially for neurodivergent individuals.

To survive socially, autistic people often suppress their true selves, leading to masking, self-suppression, and dissociation — all of which have profound mental and physical health costs.

Research collated by Russell Lehmann illustrates this stark reality:

- Autistic individuals have a life expectancy 16 years shorter than the general population.

- Suicide rates are significantly higher among autistic communities.

- Autistic individuals are more likely to experience unemployment, poverty, imprisonment, and assault.

- A study of 4,500 Swedish twins found that autistic girls aged 9–18 were three times as likely to experience sexual assault compared to their neurotypical peers.

- Approximately 80% of women and 30% of men with developmental disabilities report having been sexually assaulted — half of them on multiple occasions.

Despite societal conversations about “autism awareness,” genuine safety and inclusion for autistic individuals remain limited. Autistic people are often valued only to the extent that their talents can be commodified — for example, the popularised “autistic genius” stereotype — without true acceptance of their full humanity.

My personal experience also reflects these systemic issues. After surviving a violent attack, I received inadequate support from institutions that should have protected me. I was questioned, blamed, and then expected to continue academic work as though nothing had happened. Despite this, I later returned to support mentoring programmes at the same institution — a stark reminder of how deeply internalised these exploitative expectations can become.

This experience made clear to me: Community, in its current form, often fails the very individuals it claims to support. Community is often idealised as a place of belonging and support. However, for many — particularly women, autistic individuals, and marginalised people — the cost of participating in community is high. It can involve unpaid labour, exploitation, the suppression of authentic identity, and exposure to real harm.

As I move forward with my journey of unmasking, I aim to engage with community consciously — setting boundaries, choosing intentional relationships, and prioritising my mental, emotional, and physical health above societal expectations.

We cannot build truly safe and inclusive communities without first recognising and addressing the ways they have been built on invisible labour and overlooked harm.

Argument 3: Community Will Make You Wrong for Responding to It

As an African proverb powerfully states: “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” This resonated deeply with me, particularly as I reflect on my early teen years — a time when I struggled with nihilistic thoughts, suppressed rage, and a pervasive sense of shame. At that point, I was hiding my true self behind a mask, feeling disappointed by the people and systems around me that made the mask necessary. At the same time, I desperately sought positive examples of community.

Over time, I experienced the failures of both individuals and systems, and I tried to follow the “turn the other cheek” philosophy, as I was taught. But when I felt anger or seemed upset, I was scolded. My response, instead of being acknowledged as a consequence of systemic and interpersonal failures, was dismissed as wrong. For a period, I practiced stoicism — a philosophy focused on enduring hardship without complaint. However, this led me to take too much responsibility for the wrongs committed against me. The voice inside my head began mirroring those who had harmed me, dismissing my emotions and invalidating my experience.

A significant turning point came when I encountered the concept of grace in religious texts — the notion that humans, despite their imperfections, are still shown favor. I realized, in this context, that I am not divine. I am human, and I do not owe anyone undeserved grace. This recognition changed how I engaged with community, leading me to a more conscious, grounded approach: I now acknowledge the cost of community before making any investments and honor my emotions without taking responsibility for the harm others inflict on me.

More recently, society has started to move away from treating neurodivergent and disabled people as saints. Media portrayals now aim to represent these individuals more fully, recognizing their depth rather than reducing them to “inspirational” figures who must overcome adversity. A notable example is Elon Musk, who publicly disclosed his autism during a Saturday Night Live appearance. The backlash he received — both from the general public and even some within the neurodivergent community — demonstrated a troubling expectation: that, because of his disability, Musk should be a model of philanthropy or virtuous business practices.

While I don’t condone poor behavior, Musk’s story highlights a pattern. He faced bullying as a child, poured his self-worth into his company’s success, and still found himself criticized for his achievements. This reflects a broader societal truth: neurodivergent individuals can never truly “win” — not even in the supposed community that claims to support them.

Argument 4: Community Will Cost You Everything

A recurring issue I’ve encountered is that, when people attempt to meet the needs of autistic individuals, they often project their own neurotypical assumptions, offering solutions that don’t align with our reality. These well-meaning efforts can lead to the expectation that we return favors in ways that do not serve us. I’ve found myself pretending my needs are met, only to later feel obligated to reciprocate in ways that harm my wellbeing.

Society & Its Rules

Neurotypicals often dictate the “rules” of society, but they tend to treat these rules as guidelines rather than absolutes. I vividly remember my time in a religious community, where I adhered strictly to the rules of my faith, while others in the same group did not. This inconsistency was frustrating. One rule in particular — “turn the other cheek” — was often invoked, yet I was the one expected to practice it while others did not.

Yuval Noah Harari, in Sapiens, writes that “the truth was never high on the agenda of Homo sapiens.” This observation often makes me wonder about the implications for an autistic mind — one that is inclined to seek clarity, truth, and justice. If neurotypicals use untruths or manipulate rules for power, then the neurodivergent person must be cautious and discerning in their interactions.

Over time, I learned that rules without context are often a recipe for disaster. The context is key, and it’s often what my neurodivergent perspective missed. I now pay attention to the why behind the rules and observe how people navigate systems to understand their true intentions. This helps me protect myself and avoid falling into compliance that ultimately leads to exploitation.

Managing Society with Boundaries

This brings me to the importance of boundaries. I now celebrate every instance in which I show up for myself and set a boundary. I’ve found that, when I honor my own limits, I can move on from situations more swiftly instead of stewing in frustration or replaying scenarios in my mind. Simple actions — such as canceling plans when I’m overextended, choosing to mask only when I feel it’s necessary, or standing up for myself in the moment or afterward — have been transformative.

I’ve also adopted a question that helps me evaluate whether I’m doing something that feels harmful: If this was causing the other person as much pain as it’s causing me, would I expect them to continue doing it? So far, the answer has always been no. This has become a helpful sense-check, preventing me from needlessly enduring pain for others’ benefit.

The Case for Feelings, Intuition, and Righteous Rage

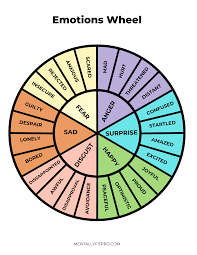

Feelings, intuition, and anger play an important role in my boundary-setting. These emotions are indicators of how I truly feel about a situation, though I also live with delayed emotional processing and Alexithymia, which makes it challenging to identify and express my emotions. To support myself in this, I use tools like an emotion wheel (example shown below) to help me articulate how I feel. I even keep pillows on my sofa with emotion wheels printed on them, so I can remind myself of this vital tool during moments of emotional difficulty.

Reconnecting to the Body Through Somatic Movement

I have found somatic movement practices to be profoundly helpful — not practices focused on fitness or aesthetics, but those aimed at rebuilding a connection to my body and emotions. For me, this looks like dancing freely with headphones on, swaying my hips without inhibition. This practice also serves as a form of stimming, which helps regulate my nervous system and emotions.

Additionally, removing the shame around feelings of anger has been transformative. Instead of suppressing anger, I now allow myself to feel it and recognize the information it conveys. I have rebranded anger as righteous rage — an appropriate and necessary response to mistreatment. I have also come to realize that people’s poor actions can and should have consequences; I am not required to tolerate mistreatment endlessly, as suggested by religious teachings such as “forgive 70 times 7” (490 times) referenced in the Bible.

My rule now is simple:

“You cannot eat the fruit of my labor if you try to chop down my tree roots.”

Autism & Community Trauma

As autistic individuals, many of us are taught early on to suppress needs that are inconvenient for others. We are told to stop crying about the tags in our clothing or stop fussing over loud noises. Over time, this distancing from our feelings leads to a chronic freeze trauma response, leaving us unable to recognize or express emotions — and even physical pain.

Unfortunately, this pattern does not end in childhood. Since disclosing my autism diagnosis, I have often encountered disbelief because of my high-masking presentation. This presents a double bind: I learned to mask to survive, yet that very masking causes people to underestimate or dismiss my support needs.

The concept of “low support needs” or “high functioning” is often used to invalidate the struggles masked individuals endure. Navigating daily life, masking at work to maintain employment, paying bills, and maintaining independence requires extensive coping strategies — many of which have serious consequences for mental health.

One such strategy has been working hard within systems to gain enough capital to secure privileges: living alone, setting my own routines, and affording coaching and therapy, since unpaid support has never been accessible to me. Even my coaching app project is an attempt to offer affordable, 24/7 support to the younger version of myself — the one who could have greatly benefited from such resources.

Self-development and coaching have always been my passions because they allow individuals to navigate from where they are to where they want to be. Recently, I discussed with my AI-powered coach on Get Coached the increasing demands in my life — a promotion, running two companies, navigating a new relationship — and how, despite appearing low support, I still have very real needs. In a coaching session, I developed a plan to better support myself: more stimming via rebounder trampolining, stricter boundaries around 2–3 hours of weekly solitude, and prioritizing my wellbeing.

Intersectionality, Autism, and Community Experiences

Finding a sense of true community has often been challenging. When I do find community, it often demands my labor and relies on the narrative that if I work hard enough, I can become “worthy” of belonging — provided I hide my needs. Rarely is the immense effort it takes to exist in these spaces ever acknowledged. Successes I have achieved are often downplayed, potentially due to the intersectionality of my identity: Black, autistic, a minority woman navigating male-dominated spaces. Overall, my experiences in community settings have been negative.

- Within the Black Community: As a Black person among other Black individuals, I have been told I am “not Black enough.” I share more about this experience in my blog post “What Does Being Black Mean to Me?” As an autistic person within Black spaces, I have also encountered the belief that autism is “not a real thing.” I discuss this further in my Instagram Live series.

- Within White, Middle-Class Spaces: In predominantly white, middle-class spaces, I have been told two conflicting things: That I am “an acceptable Black person,” viewed as an exception to racist stereotypes (with references even being made to books like The Strange Death of Europe by Douglas Murray). OR That I am ultimately not truly welcome in these spaces, particularly when I pursue hobbies like hiking, visiting National Trust sites, skiing, or horse riding — activities I am made to feel I must “justify” with expertise simply to be accepted. Class and race are often conflated, and little space exists for someone with my identity: Black, middle-class, and curious about new experiences.

- Within Female Communities: Female communities often rely on nonverbal cues and complex social dynamics. As an autistic woman with communication differences, I frequently miss these unspoken signals, unintentionally disrupting the power balance and, as a result, facing bullying — both growing up and even now. Ironically, as I’ve become more successful, former school bullies have sent me holiday-time apology messages, reflecting on their actions now that they are mothers who fear their own children facing similar treatment.

- Within Male-Dominated Communities: Navigating male spaces as an autistic and Black woman presents unique challenges. Misinterpretations of my body language — whether too much or too little eye contact, intense focus on certain topics — combined with the hypersexualization of Black women, often leads to unfortunate and uncomfortable experiences.

- Within Capitalist Structures: In capitalist-driven communities, I have found that I am valued only for my overwork and for displaying fawning responses. This exploitation — being praised for labor yet ultimately devalued — is yet another form of systemic harm.

Autistic-Led Community Reflections

Community and Autism

For me, being autistic and being in community have often felt incompatible. However, I am encouraged to see autistic-led spaces emerging, such as the Town of Taiwah, which is creating a Black and Autistic community. I am curious to see how these initiatives develop and whether they offer a more authentic form of connection for people like me.

My personal experience of community is complex. I am multiply neurodivergent, and the intersection of my conditions creates a unique experience. I tend to form intense one-to-one connections, sometimes fleeting — like a meaningful conversation with a stranger on a train who meets and matches my intensity for a brief moment.

This pattern arises from the interplay between my ADHD, which can lead to enthusiastic oversharing, and my autism, which fosters deep focus on special interests. These transient encounters meet my need for connection without the burden of long-term engagement, which often demands masking or suppressing my authentic self. Unfortunately, these types of interactions are frequently discounted because they do not fit traditional definitions of community.

At times, this has been deeply painful. I have longed for a community that truly understands and accepts me. I have questioned why I struggle to form lasting communities, why online community-building efforts falter, and whether my high-masking presentation inhibits my ability to be truly known.

Reflections on Double Empathy

The concept of Double Empathy is often discussed within the autistic community — the idea that communication breakdowns between autistic and non-autistic individuals arise from mutual misunderstandings rather than deficits solely on one side.

Research suggests that while cognitive empathy (the ability to accurately identify another’s mental state) may be different, emotional empathy (the capacity to feel and respond to others’ emotions) can be heightened in autistic individuals. This means I am often deeply affected by the emotional states of others, working hard to maintain my own equilibrium while striving to meet others’ needs.

However, reciprocity is often missing. When my needs are too different, others may default to assumptions about what a neurotypical person would require, leaving my true needs unmet. This dynamic is further complicated by the fact that, like many late-diagnosed autistic women, I have developed an intense special interest in understanding human behavior, collecting data through books, reality shows, and observation — all in an effort to “perform” connection accurately.

Despite this exhaustive effort, I still make mistakes. My best judgments are sometimes wrong, leading to painful rejections. Communities are meant to be symbiotic, not parasitic; yet too often, I find myself giving and depleting without receiving in return.

Final Reflections: Redefining Belonging

As a neurodivergent advocate, I am often flattened into a two-dimensional, “inspirational” figure, with little acknowledgment of the ongoing, complex challenges I face. These include managing the internal conflicts between autism and ADHD, as well as co-occurring conditions like OCD, anxiety, eating disorders, and pathological demand avoidance — all while striving to maintain socially acceptable body language, tone, and behavior under the heavy weight of masking.

For years, my body, mind, and spirit have cried out for me to stop seeking external validation. After a lifetime of loneliness and burnout, I am choosing a new path: building a life I enjoy on my own terms, prioritizing experiences that align with who I am. I am learning to be discerning about who I spend time with, moving away from the mentality that I must constantly perform or offer value in order to be worthy of inclusion.

I am learning to simply exist, to do what brings me satisfaction, and to hold boundaries against people and environments that drain me. I am letting go of shame around what I enjoy, abandoning the endless pursuit of proving myself to others.

I imagine a life where I laugh because something is truly funny, not to make others comfortable at my own expense. I am excited to live according to my own inner scorecard, aligning my life with my authentic self.

First, I must get reacquainted with who I truly am — after years of hiding and feeling like a puppet controlled by others. Community may come in the future, but for now, I am taking it off the agenda. I am no longer striving to be “special” in order to belong.

I am me. I am enough. I do not need to be extraordinary to be accepted. I do not need external validation or community to be okay.

As the late Robin Williams once said: “I used to think the worst thing in life was to end up all alone. It’s not. The worst thing in life is to end up with people who make you feel all alone.”